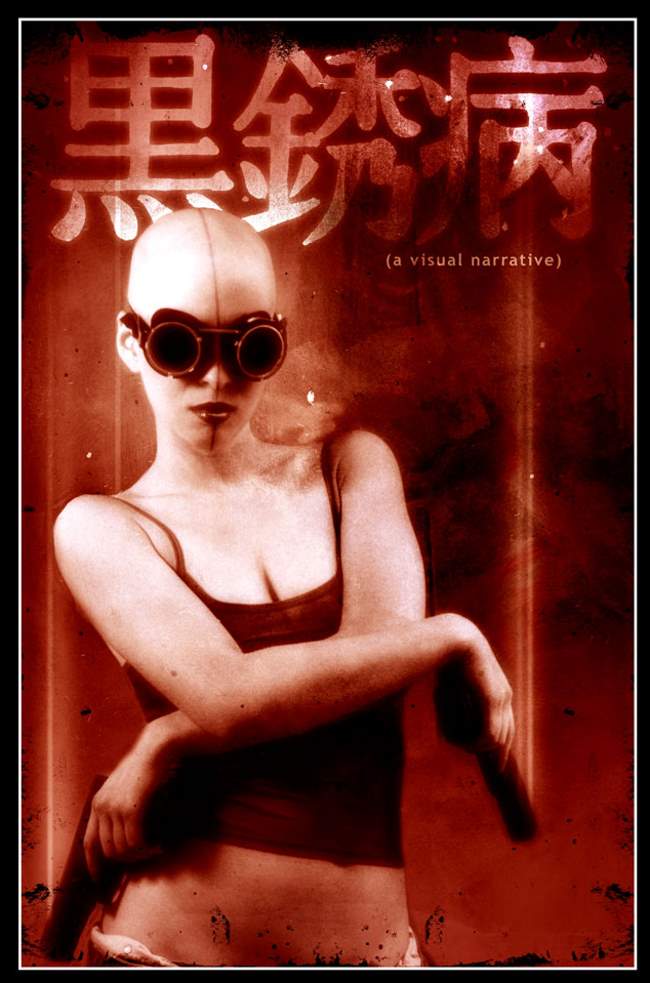

Introduction: A few weeks ago I had the immense pleasure of spending over an hour talking with Ben Steele, the director of the indie cyberpunk anime, Fragile Machine. Ben Steele, Darren Dugan, singer “X” and the rest of Aoineko created a very creative, wonderfully rich anime that deserves significantly more attention than its gotten. I refer to it as a cyberpunk operetta due to the intense interplay between the music with the visuals.

In any event, after doing the best I could at writing up our conversation, I sent this to Ben, who along with a brief read through by Darren, provided the responses you see below. This is my first of (I hope) many interviews, so I hope you enjoy.

~SFAM~

Ben Steele (Director, Writer, Music) on the left, Darren Dugan (Writer, Editor) on the right

Cyberpunk Review (CR): So how long did Fragile Machine take to make?

Ben Steele: Far too long! When I started doing animations back in 2000-2001, one minute would take me 5 months! By 2002, a 2 minute clip would take me about 4 months. Fragile Machine was planned to be three 3 minute music videos, based off a web project of mine called “Sentosa Mikano.” I thought it would take about a year. It just kept growing and growing, to the point where the finished film was 34 mins. We sped up as we went along though. In doing the film, it was a far more organic development process as opposed to a straight forward, scripted process. And I guess that while it took 3 years in total, I’d say the actual serious production time took about 19 months.

CR: How did you get into directing?

Ben Steele: I started off in visual design, and sort of went form there. Back in 2000, Aoineko was doing works for museum exhibitions, including a project called “subterranean” which was shown at the Biennal de Valencia in Spain and the National Museum of Art in Rome. Then “superelectronic” was shown in Tokyo as it had won honors in the Canon CDCC competition. As a result of that win I was featured in a national print campaign for CDCC, which was cool. Superelectronic was also exhibited at UCLA and NYU. Sentosa Mikano was produced for Ars Electronica, although apparently the picked the videogame “Rez” for inclusion instead of us (those jerks. :-P). The next project was “Living Spaces” shown at the Mugler Gallery in Paris and most recently, a very high profile event – IDN DesignEdge in Singapore. From there, we got into music videos, and eventually to animated films. Although I studied at film school, I annoyed the teachers by doing everything differently. I think this! helps in that it has allowed me to take a unique approach to film making that perhaps I wouldn’t have done had I accepted the rules of that formal training.

Aoineko came together when X and my friend/guitarist Garth started working with during superelectronic. Years later, Darren Dugan joined on, and Garth’s brothers Cliff (guitar) and John (drums, flute) both helped on Fragile Machine.

A page from the Aoineko Subterranean Museum exhibition in Spain

CR: What are your (or Aoineko’s) major anime influences?

Ben Steele: From anime, it would be Oshii (Ghost in the Shell, Innocence, etc.) and Watanabe (Cowboy Beebop), but also I was influenced by some of the classic Japanese film makers like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu. I don’t really differentiate anime film makers from live action directors. If the film is good, it can influence the direction you take. One movie that influenced me a lot was Giants and Toys by Yasuzo Masumura (1958). This film is bright and colorful with lots of satire that really captures the nuclear family idea. Another anime influence would be the composer Yoko Kanno, who is consistently inspiring to me musically.

CR: In terms of themes and visuals, there seemed to be a number of linkages to Oshii’s work. Not only the soul (ghost) within an android body (shell), but there seemed to be some linkages between your use of the elephant (which seems to represent Mary Nea) and Oshii’s use of a dog.

Ben Steele: That’s an interesting parallel because I’m actually using the elephant in my next movie as well! This blue elephant was a favored stuffed animal I had when I was a baby in my crib. I think they stand for different things, but yeah, as a convention there are definitely similarities. Though I must say, I thought the dog was a bit overused in Innocence. I found its subtle expression in the first GitS film to be more satisfying.

CR: I’m interested in this whole phenomena we see with Indie animation. Talk about the difference in making an Indie animation versus a large scale animation? We haven’t seen too many productions like Voices of a Distant Star make it big. Are we seeing this trend more favorably now? What were the key limitations you had to work around and how have you marketed Fragile Machine?

Ben Steele: Obviously the whole distribution aspects are a big challenge. But we’ve done really well targeting advertising towards niche markets. For instance, if we spent $1000 dollars on advertising Fragile Machine, we’ll always get back at least $1500 in DVD sales. But truly, most of our advertising is word-of-mouth type stuff. People don’t stumble upon Fragile Machine unless they’re already looking for something different. For those that have found it, we’ve had had a great response.

And while you don’t have the flexibility and capability as some of the larger production houses, the indie approach gives you incredible freedom in how you create your movie. I would like to see the market for these type of films increase, but mostly I’m just grateful that it’s large enough already to give me the opportunity to focus on my work completely and live the life I want. Interestingly enough, Darren Aronofsky was only paid $50,000 to direct Requiem for a Dream, and since I was also functionally the executive producer of Fragile Machine, I made a comparable amount even though the number of people who’ve seen it is about 1/100th of that who’ve seen the other film. Though I would hope he made an additional amount on royalties as well.

CR: Fragile Machine doesn’t at all “look” like a US animation; if I didn’t know where the director was located, I’d guess it was Japanese. How would you characterize an anime versus most US animated movies?

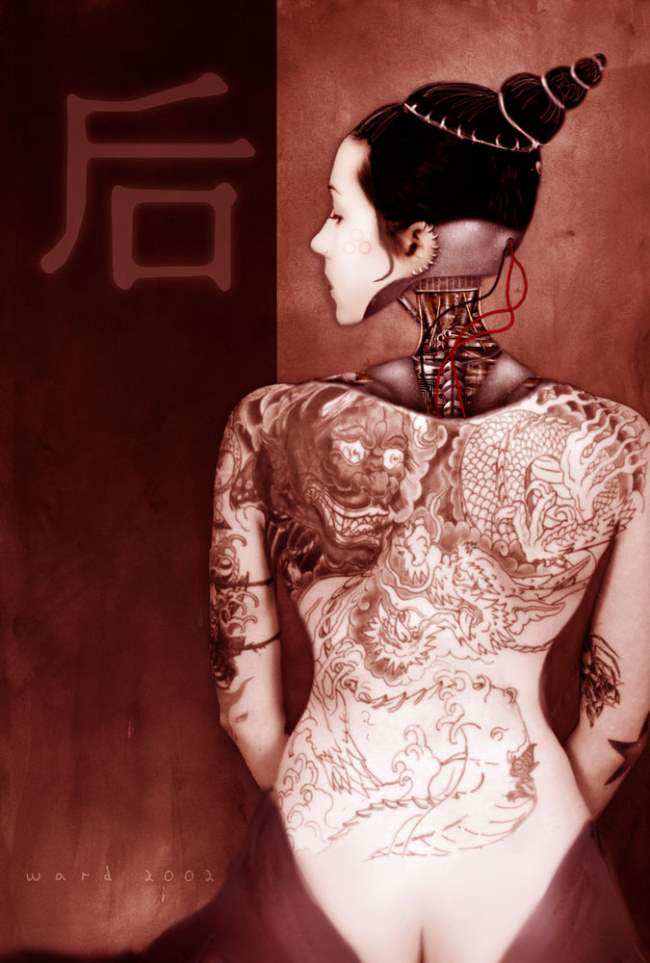

Ben Steele: The visuals in Fragile Machine overall come a mixture of the Eastern artistic tradition of Minimalism combined with the Western Baroque and Rococo traditions of oil paintings. But yeah, the definitions of anime aren’t really agreed upon by all. Some see this as a style in animation whereas others look at it purely as animation coming from Japan.

CR: The visuals in Fragile Machine are absolutely breathtaking. I’d love to know the process that generates these. Do you storyboard or do paintings prior to rendering these?

Ben Steele: Nope, no storyboarding. Visuals are designed in various graphics packages including Lightwave and Photoshop. I’m also developing a proprietary tool called the Aoineko GL which is hard to describe, but should prove to be most useful. I have an idea of what I want, but then I just take it and play with it. We often will create layers over layers to provide a complex overall effect. The end result should hopefully look like a piece of art that we can turn and look at from different angles.

CR: Your cinematography approach seems to involve lots of sweeping pans across 3D environments from various angles - it almost comes across as a bullet-time type speed. Was this in part a response to your limitations in making smooth animation?

Ben Steele: Certainly. In terms of the quality of the animation in Fragile Machine, one problem we had was I was the only one doing animation. While I love doing some styles of animation, I hate doing character animation. I find it to be very tedious work. I might spent 20 hours rendering a small environment scene and then do an entire character animation in three hours! In our next film, we’re having a lot more people involved in this, so thankfully I won’t ever have to do any character animation again (Woohoo!). With each new project, we’re adding more people and talent, and this will show. Also, you’ll see a major step up in the quality of our animation. Over the next two films, by 2010 we expect our animation quality to be on par with Final Fantasy type Advent Children style animation. You’ll see some significant improvement in our next film, and then a bit more in the second one. We’re working on the character animation skin textures! , as well as cloth and hair dynamics, for instance.

CR: Where do the Visuals of the Cityscapes Come From? These seem very similar to other well-regarded animes.

Ben Steele: Regarding the cityscapes in Fragile Machine, I spent a year living in Taiwan, and Darren visited Japan frequently. We both really love Asia and miss it. The cityscapes are my attempt to get back to that and pay my respect to it.

Fragile Machine singer “X” from a performance in Taiwan

CR: In looking at the integration of music with the narrative in Fragile Machine, clearly, a large part of the narrative is told through music. Describe this process if you could. Is this a case where you had the story first and melded the songs to accommodate, or was something else going on?

Ben Steele: Music is a big part of what I do. We’re all musicians and certainly see this as a big part of what Aoineko does. We’ve moved from music videos to animated films, but we still see the music as an integral part of the overall experience. And yeah, we certainly had an interplay between the songs and the film itself. Fragile Machine had 9 songs if memory serves. I think as we produced the animation we wrote about 30 songs and then picked the ones best suited to the story, adding emphasis to them in certain ways to compliment the narrative arc.

CR: The story comes across as more of a post-modern narrative similar to some of Chiaki Konaka’s stuff. Both the visuals and story seem to bounce back in forth almost in waves. What prompted you to use this method of story telling?

Ben Steele: We produce Fragile Machine very different from most animation houses. While we have a basic idea of what we’re shooting for, for us, the process of film making is very organic. We are constantly working and improvising with all of the scenes, and in the process of putting them together, we realize we either need more character development, more symbolic linkages or a different setting exploring some other aspect of the film. In this way, the film “grows” to become what it is. This is also reflected in the editing approach.

Fragile Machine really is a character study. It’s not story driven. This differentiates it from most anime which is mostly story driven with standard character archetypes. I really like watching classic character studies like some of Louis Malle’s works or Welles’ Citizen Kane. In putting together Fragile Machine, we really wanted to get into who she was, and what her motivations were.

CR: So do you actually consider this a post-modern method of film production?

Ben Steele: Yeah, we actually realized this midway through the process of creating Fragile Machine. In some cases this can make the process go far longer than a traditional approach. For instance, in the forest scene, Darren Dugan, who edited Fragile Machine, ended up having to edit it three times. He did it the first time, and while it looked really good, we weren’t totally happy with one of the songs in that sequence. Cliff Hockersmith and I came up with a song we liked better for that sequence, but once we put it together, it became clear that the film needed to be edited again to fit with it. After Darren did this, we ended up re-ordering the songs, which again caused Darren to edit it a third time! Which, was, ironically enough, the first song we chose after all. He was not too happy about that. While this is far from optimal, the approach does tend to make everything really fit together. You’ll notice the action in the animation mimics the rhythm in the son! gs, and often the words link up with the visuals. This would almost be impossible to plan. And truly, we find this method of free-form film making to be very liberating.

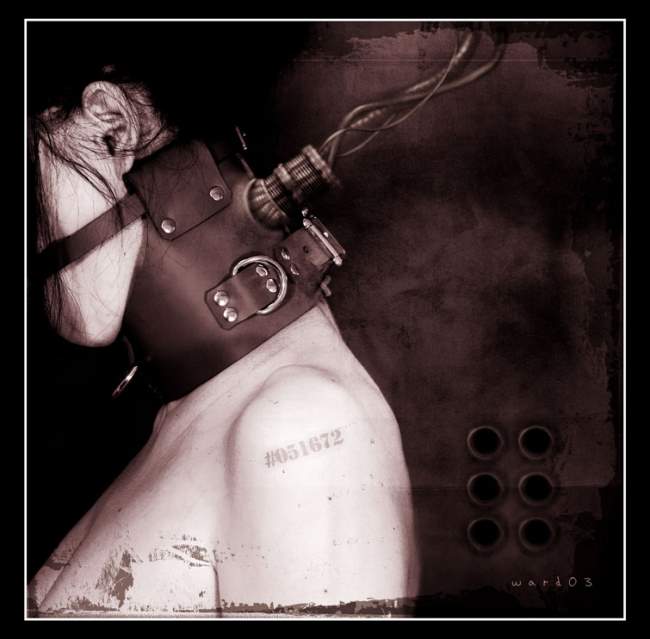

We liken Aoineko’s process of film making to be very similar to creating electronic music. Usually with rock music, for instance, there’s a structure to the song that most everyone adheres to, be it a three-chord progression, or some other format. With electronic music, you start off with a riff or a rhythm that you work into a sequence. Then you chop it up and play with it. Over time, the song “organically grows” in the process of recording and mixing. While Fragile Machine at a meta-level really follows Dante’s Divine Comedy (the android factory = hell; The forest = purgatory; the ending setting (heaven) = paradise), the story itself is very chopped up and augmented.

One post-modern character study I really liked was François Girard’s Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993). This movie deals with a real person, but tells the story in a series of vignettes, in a very post-modern way. Fragile Machine uses similar ideas in that the character study almost comes across as a series of disconnected vignettes, that, in total, gives you a sense of who Leda Nea is. We often looked at Leda Nea as being in a Diorama, in which we can see everything she does, but she often was completely in the dark. We can lift off the roof and look down on her and see what is really going on, even though she can’t see any of it.

CR: There seems to be an increasing number of post-human storylines in both movies and anime. Would you agree with this, and if so, what’s your thought on this trend, and how do you see it morphing over time?

Ben Steele: Yeah, absolutely. This is definitely an increasing trend. In real life we’re getting closer to actually experiencing this. 100 years ago, people were already thinking about this, with Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, for instance, or Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) even when there was no chance of actually doing any of this. Now, it’s right around the corner. Examples are all around us, such as the very realistic android that came out of Japan recently. In the near-future, an android will be taking your ticket when you get on your plane ride. It will be fascinating to see how young artists in 50 years are dealing creatively with the technologies they’ve grown up with, ones which we can’t even conceive of today. And I would be very pleased if in my life robotics advances to the point where greater human interaction with them occurs. Asimos flipping burgers for example.

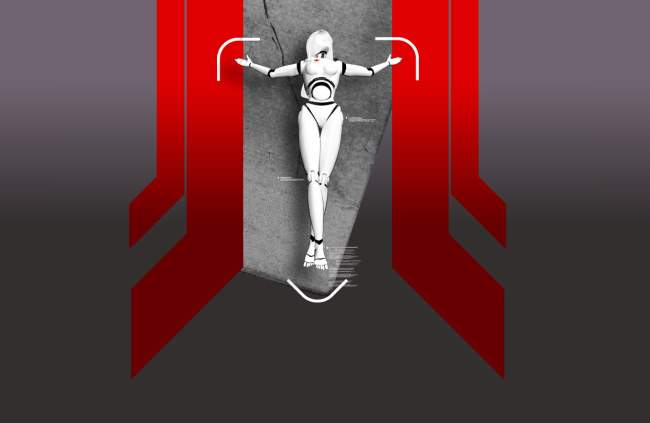

CR: Regarding the use of symbols, Fragile Machine seems very heavily symbolically laden to the point that the narrative cannot really be understood without paying attention to them. Some seem rather crystal clear, such as the challenging of God’s place (and ultimate folly of such action), fallen angel linkages, with the torture in hell type visuals, the crucifixion in nature (water) which seems to purify the soul, and of course the angels at the end. Others seem to require more thought such as perhaps the linkage of the swimming fish in the nature scene with the swimming face/data angel in the heaven portion. Others seemed like homages to other films (like the Planet of the Apes scene with the fallen face statue on the rocks being similar to the Statue of Liberty near the end). I’m really interested in the process you used for coming up with these visuals, and how this correlates to the narrative you were working to relate.

Ben Steele: It’s a natural and really fun experience. It keeps the filmmaking creative day to day. In doing the character study, symbols are a good way to show how everything fits together. The symbols really are a product of the spontaneous, organic film making process. For instance, the Tree of Life in the Forest scene represents heaven, which we see Leda Nea going towards after she leaves her body in the last hell scene. The swimming angel fish in the water mimics seeing Leda Nea as an angel in the later scene where she’s just a face with datastreams behind her, swimming in heaven. I often wish we could do a show where they have nine screens of Fragile Machine running on a constant loop because we have so many scenes and symbols that echo scenes and symbols later in the film, chances are, people would see linkages between the scenes simultaneously.

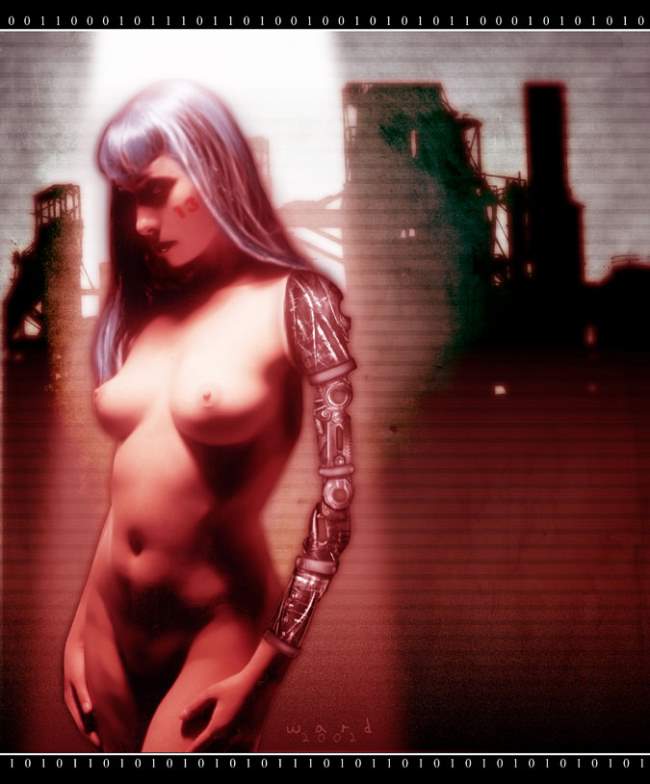

CR: The idea of embedding a soul within an android body has been the grist of a decent number of stories and movies, each one taking a slightly different tact. What attracted you to the idea of embedding a soul into an android?

Ben Steele: Part of this deals with the idea of relating a spiritual story in a completely different setting. I find it boring to think that we’re all there is, that there isn’t anything that happens after we die. Perhaps post-post modernism, whatever it will eventually be called, will be the “nihilism is boring era.” jk

But doing a straight-up realistic anime that deals with religious aspects could easily run the danger of coming across as preachy. In placing the spiritual aspects in the context of an android with a soul, we’re able to bypass people’s biases. Especially as our interest is “spiritual” rather than “religious”. Theology to me seems inherently limited, yet in a certain context it can be elucidating.

CR: Fragile Machine deals with some very interesting religious ideas. One musing I took away from this that was unique is if an android had a soul, what would happen to it when the android dies? If you could, describe the religious message you wanted to get across.

Ben Steele: Really, we’re far more interested in getting people to think about the same questions we have versus providing them with a message. In bringing up religious or spiritual themes, there’s always a danger of coming across as too preachy or dogmatic. We worked hard to avoid that, and were worried at times whether we would be seen as crossing some invisible line. For instance, when we inserted the comment, that Leda Nea was the “first person to made by man instead of by God” we had a discussion of whether this would offend some, but in the end, we decided it was critical for the story.

In terms of science fiction, we take a spiritual-humanist approach, which is actually very rare. Very few science fiction stories focus on anything other than living beings. Most seem to assume that this is all there is. Although the Matrix Trilogy certainly raises these questions, it does so in a metaphorical way, whereas we explicitly include it in the story. To me, I would see life as being kind of pointless if I thought there was nothing after we die. For instance, when I heard John Lennon’s Imagine as a child, I ended up thinking the entire message was kind of lame. Whatever it is, when we die, lets hope SOMETHING happens!

CR: What prompted you to decide to make redemption the central theme of Fragile Machine? Was this an upfront decision?

Ben Steele: Yeah. That’s definitely what Fragile Machine is about. This was something we really wanted to explore. In many ways this is a personal story about X, the singer for the songs in Fragile Machine. When she grew up, her mother was severely mentally handicapped and couldn’t really speak to her. X lost her mother and never really got closure. Interestingly, she had a very personal experience after her mother died in which she actually got to speak to her mother through a surrogate, and was able to come to closure. As many times as she’s seen it, X still cries when she sees the ending of Fragile Machine. In a sense, this was an opportunity for redemption for her mother, to set things right. Fragile Machine takes this same concept and reverses the characters, thus altering the context.

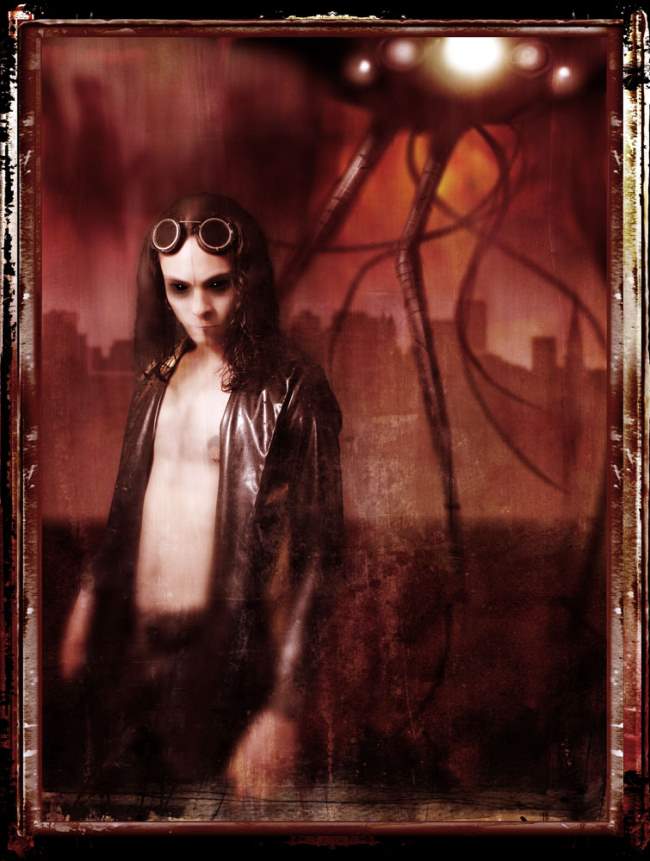

CR: Regarding future projects, what’s Aoineko working on now? Anything we might consider

“cyberpunk”?

Ben Steele: The next film is going to be more of a story driven approach, which will be a challenge from an organic filmmaking standpoint. Currently, its code name is “Charity.” I guess if I was pitching it to some Hollywood producer I’d say “It’s a futuristic slacker road trip movie!” but that is a pretty superficial description that wouldn’t do the emotional intensity of it justice. We’re not sure if Charity will be the final movie name as this would be similar to naming Fragile Machine “Redemption” instead. It’s not as dark a story as Fragile Machine is, but there are a lot of cyberpunk themes involved. Interestingly though, the future setting will be more background in that the characters will just be taking it all as a given instead of the “wow” factor some SciFi movies show. I mean, no one in the real world walks around thinking “wow, cars are so cool!” so how come in the sci fi movies the characters alw! ays seem to think the spaceships are so damn interesting?

Mixing forward narrative with organic growth or postmodern narrative requires a new type of structure but hopefully we can find a balance that allows us a good degree of flexibility in modifying and growing it as the production proceeds. We have an idea for the film after Charity, one that’s a bit darker and will deal with even more cyberpunk themes but I really don’t want to give anything away right now. You’ll just have to wait on that!

CR: Ben, I’ve truly enjoyed talking with you. Best of luck to you, Darren and the rest of Aoineko.

Ben Steele: Thanks again SFAM. It was a lot of fun.